I’m Not Really A Ligne Claire Artist

Ligne claire and clear line are terms used interchangeably in the art community when talking about that beautiful comic-book style, that power-couple of heavy black lines and bright colors. I’ve always referred to my own art style as ligne claire, but it’s recently come to my attention that I can’t really call my style that.

So what is my style called? Well, it’s a combination of all the comic books I’ve ever read. Like every style, my style is not just one thing.

But what is it about this style of linework and color that I find so appealing? Is it that you instantly know what it is when you look at it? Is it that you don’t find it in galleries, but in picture books and posters? Is it that whereas gallery art goes for millions, you can buy a comic book for a buck fifty? I’m going to get into all that, but before we begin I want to look briefly over the history of ligne claire and comic book art.

Woodblock Printing

When we think of woodblock printed images, we probably imagine Gutenberg Bible illustrations, or the adventures of Tom Sawyer. But woodblock printing goes back to around 200 A.D., in China. It eventually transitioned into Ukiyo-e art, which I will cover in a later secition.

Image-printing technology has been used for almost two thousand years. Originally used to distribute literature, it also became the medium for mass-producing images, ultimately cheapening art.

Printed images have a sharp quality to them that I’ve always loved. It’s this same sharpness that can be found in the ligne claire style, which is what we’re going to discuss next.

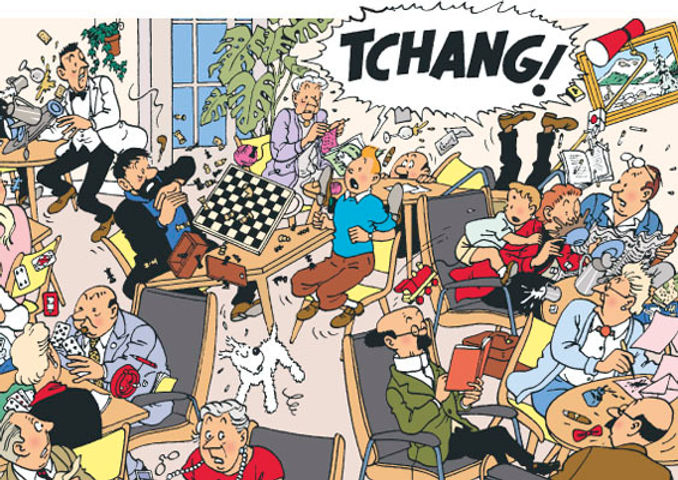

Hergé

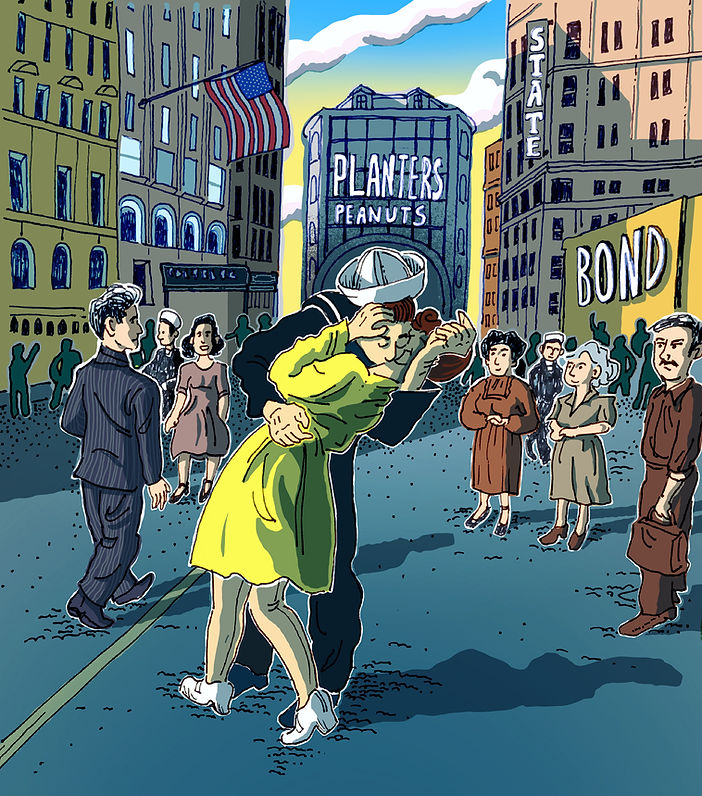

Georges Prosper Remi, better known by his pseudonym, Hergé, was a Belgian cartoonist who is accredited with the “invention” of ligne claire. Though he created multiple comics, his most famous by far is The Adventures of Tintin

Along with character development and a consistent sense of humor, the visual detail Hergé put into each panel of Tintin was mind-blowing. Fully-formed cities rise off the pages, almost in 3D. Every button is drawn on every coat, and every tree is outlined perfectly. Rocket ships, tanks, and jeeps are vignetted in perfect perspective, set in heavy black lines.

He was a master of taking the image in his head and putting it on paper.

Though reports of Tintin’s inspiration are sketchy, it’s speculated that the comic series is inspired by Palle Huld, who traveled around the world at age 15. This is a credible postulation, given Tintin has a very strong travel/international flavor. The Castafiore Emerald is the only book that doesn’t involve travel abroad. Hergé’s images take you on a journey around the world.

So it’s no surprise I eventually chose a life abroad.

Some moments in my childhood stand out more clearly than others, and one such moment is my mother commenting on how detail-rich my drawings were. That observation stuck in my brain like a popcorn kernel in teeth. I guess I kept coming back to it—my strong suit was in the details. I loved drawing anthills filled with furniture, and in my teenage years became obsessed with lines in the human face. I still love drawing complicated architecture, and find drawing hair strand-by-strand a zen activity.

Maybe these are reasons why I was so drawn to The Adventures of Tintin, or maybe Tintin is the reason I turned out like I did.

Some of My Favorite Artists

Hergé is my obvious pick for ligne claire hero, but many others spring to mind, both European and American. Here are a few favorites.

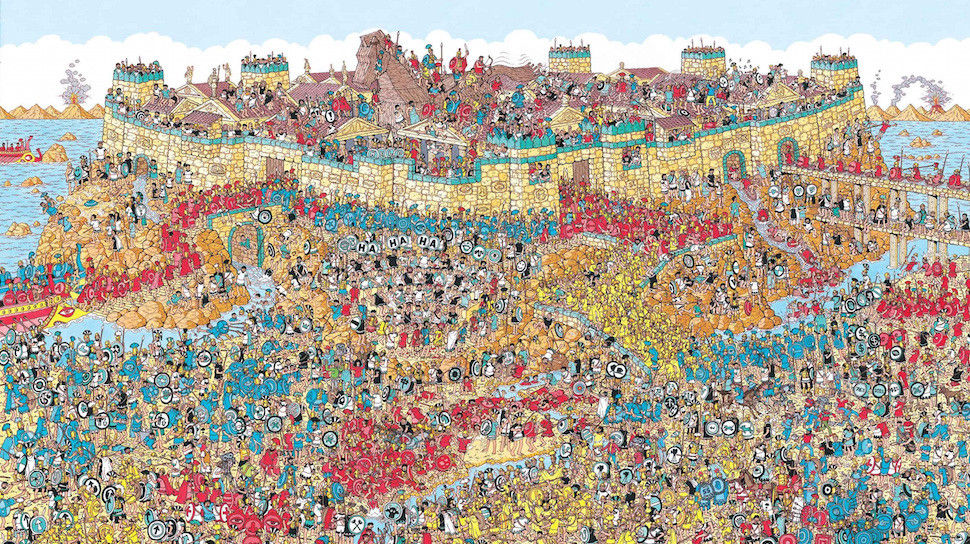

Martin Handford

Where’s Waldo (At this point I’m equally used to calling him Wally—I never understood why it was changed to Waldo for us Americans) was another favorite book of mine growing up. Even if I memorized where Waldo was on the page, I still loved getting lost in the pages. You could get stuck in there for days, it seemed.

Mœbius

I’d be a blind clam if I didn’t applaud Jean Girard’s hardworking technique. Some consider him one of the founding fathers of comic art. You can find the works of mœbius here: https://sites.google.com/site/moebiworld/home

Guy Billout

Guy’s conceptual work challenged ideas of reality, and often put people in an odd situation in the middle of nowhere, completely by themselves. There’s something sad about the worlds Billout created, but his coloring and the straightness of his lines is relaxing. (I finally learned how to say his name right when I was working as a waiter at a diner, and heard a customer pronounce it ghee beeloo.)

François Place

Browsing the art section of a Taipei library is where I stumbled upon L’atlas des Géographes d’Orbæ. As the book was in French and Mandarin, I had to slowly come to the realization on my own that he was imagining worlds on paper. I have yet to come back to his work to see what was really going on, but his idea of place and space was enthralling.

Bill Watterson

Bill created the iconic Calvin and Hobbes, a comic book that defined my childhood. Like me, Watterson was not formally educated in art. His comics centered around imagination and whimsy, and fueled many childhood art endeavors for me. In 1995, he retreated from comic strip art and has spent the rest of his life away from the public eye.

Ukiyo-e

While my artwork definitely lacks the perspective work, perfectly straight lines (I don’t like using rulers), and preparatory pencil sketching to put it on the same level as ligne claire, I do retain the same obsession with sharp lines and contrast. That’s where ukiyo-e comes in.

Lest I commit the gravest social sin of the 21st century—dwelling too long on European masters to the neglect of the rest of the planet—now is a perfect time to bring up ukiyo-e, a Japanese combination of woodblock prints in layers of ink.

While ligne claire is a trend that began in the 20th century, ukiyo-e came on the scene in the 1600’s. Ukiyo-e is the marriage of the sharp lines of woodblock printing and a color-printing technique called bokashi that allowed for color gradients.

Incidentally, Hergé was also inspired by ukiyo-e prints.

Why Lines?

I’ve worked in watercolor before, but the contrast between my painted images and my digital images is stark. I tried watching watercolor tutorials, and it wasn’t long before realizing that paint just wasn’t my medium. Even when working with paint, I wanted those hard lines—I needed distinctive boundaries between colors, definition of what went here and what went there.

Soon, I started to realize that my whole life, I’d been employing this obsession with lines not just as an art style, but as a philosophy. I like music with clear chords and well-defined vocalization, such as the works of Adam Young, Postal Service, Secondhand Serenade, or George Gershwin and Cole Porter. In clothing, I prefer structured garments over silky, swishy materials. When cooking, I love putting each food in its own little plate or bowl, like Japanese cuisine does.

It’s just all about the lines.

Even the main premise of my fantasized life abroad fixates on the idea of international borders—lines between countries, one might say.

I slowly came to the realization that I like line-based art because it portrays the world as I see it. Did I come to these philosophies based on the art I digested while I developed, or was I drawn to these styles because of a preexisting mentality? Without some kind of time machine that lets you see into alternate timelines (see? I can’t get away from it), it’s impossible to say if the chicken came first, or the egg did.

The best pathway to finding good style is finding your own style. But whether I found this art style, or it found me, I think we’re a perfect match in and out.

Art & Classism

Since the genesis of woodcuts in 200 A.D., printing has always favored mass production, which translates into affordability. Gallery art is a racket often disconnected from the pedestrian multitude. However, woodcut prints, and therefore comics, have always been for the masses.

I don’t want to sell a blank canvas with a single spray of orange paint on it for a million dollars. (Though if that did happen, I wouldn’t refuse the money.) What I’m saying is—and maybe this quote will come back to bite me—I want to work hard on something that can be mass-produced and bought by regular people for the cost of a sandwich.

My professional hope is that someday, a child can see something that I made, and it can influence them for good, in the same way that Hergé, Watterson, and Handford influenced my own childhood.

When art is accessible to the working-class, it becomes accessible to children. And when art is accessible to children, it has the power to change the world.

Leave a comment